The topic of behaviour management and the problems teachers face in dealing with disruption to lessons continues to evoke strong argument within the profession. The extent of the problem was explored in a 2014 paper by Terry Haydn which argued that whilst ‘official’ reports like Ofsted inspections appeared to rate behaviour as at least ‘satisfactory’ the majority of schools, there was evidence that deficits in classroom climate continue to be a serious and widespread problem. Examples of blogs detailing the sorts of issues in school approaches to behaviour are plentiful (an excellent example from Andrew Old can be found here).

Systems of rewards and punishments have long been the norm in schools but perhaps because of a growing feeling that behaviour has become increasingly difficult to manage, behaviour management has become the focus of experimentation. Some schools have started looking for novel solutions to the problem of disruption in lessons (e.g. Kilgarth school in Birkenhead was recently reported to have ‘banned’ punishment altogether). Whereas, others believe that proportionate sanctions need to be available to teachers as a deterrent (e.g. Tom Bennett urging “schools to bring back detention”). In June last year, the government set up a working party, led by Tom Bennett to develop better training for new teachers and showcase effective practices in schools. For an example of Tom’s approach, there’s a nice practical guide to managing difficult behaviour recently published by Unison.

One controversial approach has been to move schools away from systems of reward and punishment towards a ‘Restorative Justice’ approach. Originally developed within the context of police work, the idea of restorative practice involves conversations between ‘offender’ and ‘victim’ or the teacher and student to give an opportunity to discuss how they have been affected by events and to decide what should be done to move forward. There are claims that this approach can improve behaviour and results, but critics argue that such policies are making schools less safe. Whilst not always explicitly linked, many of the processes appear to draw upon techniques used in cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). For example, ‘Restorative Thinking’ is a team that work with schools to implement school restorative practices that make the link to CBT and other forms of therapy explicit.

Another controversial approach has come from Doug Lemov’s ‘Teach Like a Champion’. Lemov’s approach involves using standardised routines to create a positive classroom climate. The system has sparked considerable interest in the UK, but also many critics. Perhaps most notable amongst these critics is Sue Cowley, author of ‘Getting the buggers to behave’ who recently condemned* an example of this approach as “a kind of ‘Pavlov’s Dogs’ approach to education”.

(*Edit – However see Sue’s comment below)

Most teachers likely already use some combination of these various approaches, but teachers may not be aware of the psychological theories and practices which they are (implicitly or explicitly) based upon. Over a short series of blogs, I want to briefly explore these psychological underpinnings in the hope they help explain some of the advantages and limitations of each system.

Part 1: Behaviourism

“Behaviourist” is sometimes used in a pejorative way when describing behaviour management systems, but schools using some sort of system for rewarding or sanctioning behaviour are implicitly using a behaviourist approach.

Behaviourism was a term coined by John Watson in an article published in 1913, but its roots go back to the famous studies by Ivan Pavlov (who discovered Classical conditioning as an accidental side-line to his Nobel Prize winning research on digestion). However, the behaviourist most associated with education is B. F. Skinner. Much misunderstood, and often unfairly maligned, his theory of operant conditioning continues to influence schools to this day.

Drawing on the earlier work of Edward Thorndike, Skinner developed his theory of operant conditioning by exposing animals like rats and pigeons to carefully controlled stimuli and recording their responses (what’s often referred to as a ‘Skinner box’). Skinner identified a variety of techniques which could be used to shape animal behaviour and wrote about how these might be applied to human behaviour (and education specifically).

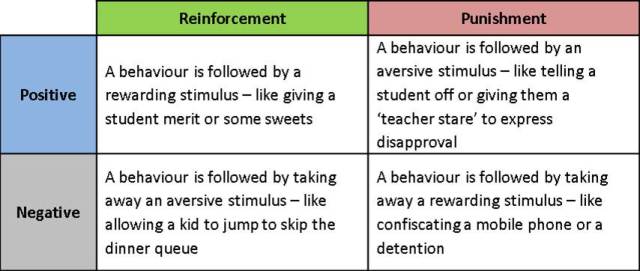

The core idea within operant conditioning is reinforcement and punishment. Very simply, when an animal receives reinforcement after performing a behaviour they are more likely to repeat that behaviour. Conversely, receiving a punishment after performing a behaviour leads the animal to be less likely to repeat that behaviour in future. Skinner further described reinforcements and punishments as being ‘positive’ or ‘negative’ in character.

Punishments

Skinner’s rather harsh reputation means that many teachers are surprised to discover that he was very much against the use of punishment in schools. Skinner believed that one of the major disadvantages of punishment is that, even where it is consistently applied, it merely temporarily suppresses an undesirable behaviour.

“Severe punishment unquestionably has an immediate effect in reducing a tendency to act in a given way. This result is no doubt responsible for its widespread use. We “instinctively” attack anyone whose behavior displeases us —perhaps not in physical assault, but with criticism, disapproval, blame, or ridicule. Whether or not there is an inherited tendency to do this, the immediate effect of the practice is reinforcing enough to explain its currency. In the long run, however, punishment does not actually eliminate behavior from a repertoire, and its temporary achievement is obtained at tremendous cost in reducing the over-all efficiency and happiness of the group.”

Science and Human Behaviour, p190.

Contrary to his rather cold, clinical popular reputation, Skinner was a compassionate humanitarian (he won The American Humanist Association’s “Humanist of the Year” award in 1972) who wanted science to help shape a better society by utilising rewards rather than punishment in order to promote pro-social behaviour. I suspect he’d have approved of Kilgarth school’s decision to ‘ban’ punishment, for instance.

However, the issue around the effectiveness of punishment is rather more complex than Skinner believed. For example, a fascinating meta-analysis by Balliet and Van Lange (2013) examined whether punishment was more effective at promoting cooperation in high or low trust societies. They reviewed 83 studies involving 7,361 participants across 18 societies and found a rather surprising conclusion: Punishment appears to effectively promote cooperation in societies with high trust. In essence, they argue that where there is a great deal of trust, members of a society adhere to norms that encourage both cooperation and the punishment of those who defy cooperative social norms. Punishment is less effective in societies where there is a lack of trust: They argue that social norms may be less strongly shared and enforced and so punishment may be less effective in these societies.

“A willingness to pay a cost to punish others, especially noncooperative others, is likely to be viewed as a strong concern with collective outcomes. At the same time, such benevolent views of costly punishment may be more likely to occur in societies that contain higher amounts of trust in others, which we conceptualized earlier in terms of beliefs about benevolence toward the self and others.”

An important question for future research is whether ‘benevolent punishment’ is as effective at an organisational level (e.g. a school) as it appears to be at a society level. However, the implication would be that in benevolent, high-trust environments the proportionate use of punishment to support cooperative social norms can be effective.

Another reason why punishment may be effective is a phenomenon called ‘loss aversion’. The work of Tversky and Kahneman suggests that there is an asymmetry between the effects of positive reinforcement and negative punishment – in that where people weigh up similar gains and losses; people tend to prefer avoiding losses to making gains. For example, Hackenberg (2014) Token Reinforcement: A Review And Analysis, reports an experiment where the value of a loss was worth approximately three times more than a gain. It seems highly likely that this effect might also apply to the sorts of token reward systems employed in schools; suggesting that negative punishment (e.g. loss of merits) may be more motivating than opportunities to gain merits.

Rewards

Skinner believed that rewards were the most effective way of shaping behaviour and focused a great deal of his research attempting to find out the most effective patterns of reinforcement. In his ‘Skinner box’ experiments, he was able to carefully control the ‘schedule of reinforcement’ and measure the concomitant changes in the desired behaviour.

Intuitively, teachers see the need for consistency where punishments are applied and I’ve sometimes heard teachers argue that rewards should be given with equal consistency. However, Skinner’s work on ‘schedules of reinforcement’ appears to show that such systems tend to be relatively ineffective. The problem with systems seeking high consistency in rewarding students is that whilst the student’s behaviour may be swiftly modified, the desirable behaviour may become highly contingent upon the presence of the reward. The odd thing about rewards is that they appear to work better when they are slightly unpredictable. A simple summary of these differences:

In Skinner’s experiments, the extinction rates (the rate at which the desired behaviour stopped being performed) was quickest where there was continuous reinforcement (i.e. a reward given for every time the behaviour was performed). Where there was variability in the time interval or ratio, then the behaviour persists for longer in the absence of reinforcement. Skinner believed this represents the ‘power’ of the slot machine. The fact that playing it is unpredictably rewarded by a pay-out encourages the person to continue playing – even where they hit a long streak of losing.

In schools, sometimes these reward systems take on the structure of a ‘token economy’ (systems also used in prisons and psychiatric units – where individuals earn tokens for ‘good behaviour’ which can be used to purchase privileges). However, whilst explicit reward schedules have been used with children (e.g. children with ADD or Autism for example), reward systems have a number of problems which often undermines their use in schools.

One issue is ‘satiation’ – particularly older children rapidly lose interest in the tokens (e.g. merit stickers) or even primary reinforcers (e.g. sweets) that teachers hand out for desirable behaviour. I recall a student teacher handing out sweets to reward year 10 students for answering questions in class. Many of the students took part, but I noticed one lad sat there scowling with his arms crossed. Chatting to him, it was clear he knew many of the answers so I asked why he wasn’t putting his hand up – he said, “What’s the point? I can just buy my own sweets if I want them”. This problem often leads into what I call ‘reward inflation’ as teachers either have to constantly find novel rewards or end up handing out more and more tokens to elicit the same desirable behaviour.

Another issue is that reinforcement can have negative effects. It’s devilishly hard in a class of 30 students to accurately assess how much effort students have genuinely put into their class or homework. Giving praise or a merit for work which actually required little effort may inadvertently imply that you have low expectations of that student.

Lastly, children aren’t stupid. They rapidly learn when they are being manipulated by a reward system and sometimes manage to turn the tables on the teacher by learning to manipulate the criteria used to elicit a reward. I knew one teacher who, in an attempt to tame a particularly difficult class, had managed to trap themselves into handing out 4 or 5 merits to a number of the most naughty children every lesson.

Two great articles by Daniel Willingham further explore some of these problems: Should Learning Be Its Own Reward? and How Praise Can Motivate—or Stifle. At the end of this second article, Willingham summarises the way a teacher’s most common form of positive reinforcement – praise – might best be utilised:

“Praise should be sincere, meaning that the child has done something praiseworthy. The content of the praise should express congratulations (rather than express a wish of something else the child should do). The target of the praise should be not an attribute of the child, but rather an attribute of the child’s behavior.”

In summary

Whilst the term ‘behaviourist’ is used in a pejorative way by some teachers, Skinner desired his research to be used to create societies where reinforcement was used to encourage people to do the right thing, rather than punishment. There’s an enormous amount schools could potentially learn from the classic works on operant conditioning and ways to run token economies (which most school reward systems tend to form).

However, there are some interesting reasons why some of Skinner’s ideas may need updating. ‘Benevolent’ punishment and negative punishment (which may tap into our innate loss-aversion bias) may in some cases be equally or more effective than rewards (so long as they are deserved but a little unpredictable). Both potentially can be used to effectively support behaviour in schools.

In the next post in this series, I’m going to take a similar look at the topic of ‘restorative practices’ and some of the ideas from cognitive-behavioural therapy which underlie many of the systems used in schools.

Reblogged this on The Echo Chamber.

LikeLike

This overlaps with a post I am writing on motivation. I too like Willingham’s perspective on rewards and motivation. Thanks for this excellent and typically helpful blog.

Alex

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think ‘condemn’ is quite an emotive word for the questions I was asking in that blog. Where an approach is going to be used on one group of children and not on others, I believe we have some serious questions to ask ourselves about both ethics and efficacy. Is it okay for us to use an approach that requires high levels of conformity, on only one part of the school population? Movement is a key part of the way in which small children learn and develop. If we are going to proscribe the type and amount of movement we allow, we need to be sure that it is a good idea physically, psychologically, intellectually.

LikeLike

Likening the responses of students to Pavlov’s dogs seemed a pretty fierce condemnation to me – but I apologise if I’ve overstated your position on the system.

LikeLike

It was meant as a non emotive point – a Pavlovian style stimulus and trained response is what lies behind these methods, literally. We do this already in schools (e.g. ‘call and respond’). My take on it is that we need to question the ethics of how far it is okay for us to go with this approach and also when it stops being appropriate for children’s healthy development.

LikeLike

Actually, I disagree that such techniques are ‘Pavlovian’. In a future blog post I’ll explain some of the psychology I think underlies them in more detail, but I think they are based on normative influence and social cognition more than behaviourist ideas (and certainly not classical conditioning).

Like my reply to Tim O’ Brien (below), I accept there’s debate here. Some people are deeply troubled by schools using systems to elicit compliance. I agree there’s a question of degree – and my hope is that discussing some of the psychology underlying these approaches will inform that debate.

LikeLike

Yes, I think it’s a very useful debate to have, thank you for this blog post. Our discussions have in part inspired me to write this blog https://suecowley.wordpress.com/2016/01/10/power-play/. The question I suppose is partly how far we want to try to teach behaviour, and how far we want a system that will (try to) do most of the work for us. I think there are some pretty serious ethical questions that we need to ask about levels of student dignity and agency in the ways that we manage behaviour. I think the real sticking point of punishment based systems comes because of exclusion and I’m not sure how we can square that with the concept of inclusion. I find that when I read about school systems, they often don’t follow that bit of the question through to its logical end point.

LikeLike

What, if any, evaluation of the techniques in Getting the Buggers to Behave is there in terms of physical, psychological and intellectual effects? Have you actually met the high standards you demand of others? Because it is easy to scare monger so that your own methods and techniques are seen as superior. Please don’t pretend to be value and interest free in this debate – you’re really not!

LikeLike

Firstly, I want to say that this is an interesting and informative post.

I would also like to say that I have serious concerns about the way Behaviourism has been (and probably still is) applied in SLD settings. I can see Sue’s points about conformity. My concern is the use of Behaviourism as a methodology of controlling young people who have severe learning difficulties (with associated communication difficulties). The locus of control is always with the teacher and that meets the needs of teachers who use control as a way of avoiding the difficult thinking around how to meet the needs of a young person with SLD in a different way.

There are associated issues about what the person is actually learning. I have seen people with developmental delay being given Smarties for making eye contact – because eye contact is perceived by the school to be a socially acceptable way of communicating. When the smarties are taken away the young person stops giving eye contact. They have not learned how to give eye contact in social settings, they have learned that eye contact produces an edible reward and when that reward is removed they change their behaviour.

Finally, I don’t think that behaviourist approaches should be applied in any school setting. The issues around control and at times disrespect are amplified in settings for those in SLD schools. I will also add to why don’t I agree with it in school settings issues around independence, independent learning, problem solving, the ability to self-regulate…. (the list continues)

LikeLike

Thanks for the comment. Yes – I recognise that for some the issues of using rewards or sanctions to elicit compliance are problematic enough that they feel such systems should be avoided altogether.

Whilst I recognise that you and others feel that such techniques are troubling, it’s clear that many teachers feel that using systems which encourage a degree of compliance are justified when applied for the benefits of that student and the wider school community. At the last, these systems are used in the vast majority of schools – so explaining some of the behaviourist principles implicit in their use is important I think.

LikeLike

I enjoyed the summary.

Science of the type used by Pavlov and Skinner is very useful when it simplifies impossible complexity, identifies recurrent links or suggests new questions. Once achieved however, the simplification needs to be suspended so that all the other variables of the social context of teaching can be addressed, and their contributions assesed. There are plenty of systematic studies of the social values and group behaviours that can be experienced, and sometimes changed, in classrooms (Paul WIllis http://www.amazon.co.uk/Learning-Labor-Working-Class-Morningside/dp/0231053576 was a favourite of mine but there are many others).

One other kind original source that might be added on the social/intersubjetive side of enquiry that balances “hard science” is the practice-inspired writing of Carl Rogers who suggested the pre-conditions within which simple behaviourism might sometimes work but (in the absence of which) will almost certainly be thwarted. Both the classroom teacher and the wider school context would need to be genuine, trustworthy (and trusting) and appreciative of pupil or student intentions and feelings. As the PDT slogan used to have it: Genuineness, Trust and Empathy.

To put all that another way, once you think you’ve cracked it, along comes a pupil or a class who find out how to crack you. Youngsters learn very quickly, however hard you try to stop them. At some point you have to be straight with them, for your own good if not theirs.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the comment and the link.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on From experience to meaning… and commented:

A good summary with some nice updates!

LikeLiked by 1 person

A very helpful summary.

Could you expand on the distinction between positive/negative reinforcement and reward/punishment? When I was learning about behaviourism, the terms ‘reward’ and ‘punishment’ were rarely used. Didn’t think about it at the time, but with hindsight I think it might have been because ‘reward’ and ‘punishment’ have moral overtones but people and animals don’t always learn in a moral context. So, behaviours can be positively or negatively reinforced by chance, not always because they are actively rewarded or punished.

I think this is an important distinction because ‘reward’ and ‘punishment’ are highly salient in schools but students might acquire certain behaviour patterns due to circumstances that the school wouldn’t classify as ‘reward’ or ‘punishment’.

Take school toilets as an example. Every school I’ve ever encountered has found the toilets a behavioural challenge but student behaviour in relation to toilets is often shaped around factors such as cleanliness, whether the doors lock, access, and level of supervision, not around ‘reward’ or ‘punishment’.

LikeLike

Hi – I’m not sure BF Skinner would make the distinction you appear to be trying to make. Reinforcement and punishment do not necessarily require ‘moral agency’. For example, he points out that a child putting their hand in a flame would receive ‘punishing’ feedback. Non-moral reinforcement might be positive like enjoying some chocolate, but can also be negative – like taking a painkiller.

The point you make about student behaviour in the toilets is an interesting one. I agree, it’s not easily explained through operant conditioning. Instead, I’d explain it through social norms – which will be the subject of my third post in this series.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: The psychology of behaviour management (part 2) | Evidence into Practice

Pingback: Psychology of behaviour management (part 3) | Evidence into Practice

Pingback: Blogs of the Week – 15 January, 2015 | Rhyddings Learning Power